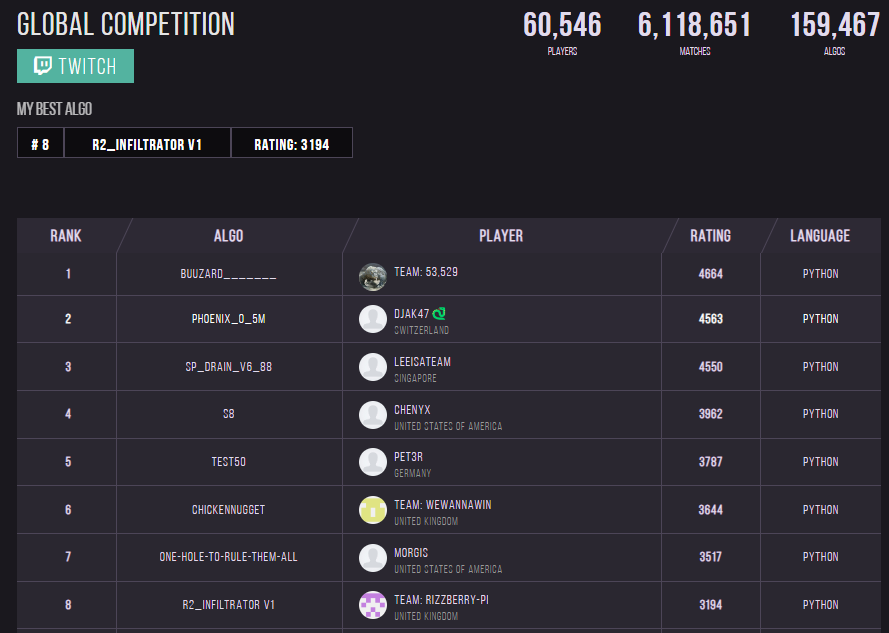

Our algorithm,

Our algorithm,R2_INFILTRATOR, (in red) defeating the world no.1 algorithm on the Season 8 global leaderboard.

During my 1st year summer term, I took part in a European regional competition, where 32 teams from all over the continent designed and coded algorithms to play a tower defence game called Terminal. Our algorithms were pitted against each other at the end of the week-long competition, where my team consisting of a friend and I achieved 6th place. After the competition, we spent some time adjusting our algorithm, where we achieved 8th position on the Season 8 Global Leaderboard.

Understanding the Game

A game designed by the company Correlation One, Terminal is played on a diagonal board, where players place down defensive structures and assaulting units each turn. Each player is trying to prevent the opponent’s units from entering the diagonal edges on their side of the board, while trying to score on the opponent.

The game is played over multiple rounds, where players are given a limited number of points each round to buy or upgrade units.

Design Challenges

Initially, we were quite overwhelmed by the game, where we had to familiarise ourselves with the complex mechanics of the game and pore over the algorithm documentation. There was a vast array of choices each turn, such as deciding to upgrade existing units, deciding where to place new units or deciding to remove old damaged structures.

Further, the game was designed such that both players plan out their rounds simultaneous. Hence, it was not possible to know your opponent’s strategy for that round, where we could only infer based on the last round.

Deciding a Strategy

Given the short amount of time and the large range of possible decisions to make, we decided that it was infeasible to come up with a meaningful and working model in time based on all the game state information.

By observing past year team strategies and examining the board, we instead simplified our strategy by exploiting three key features of the game: asymmetry in defensibility of positions, predictable path-finding of the assault units, and high damage potential from self-destructing assault units.

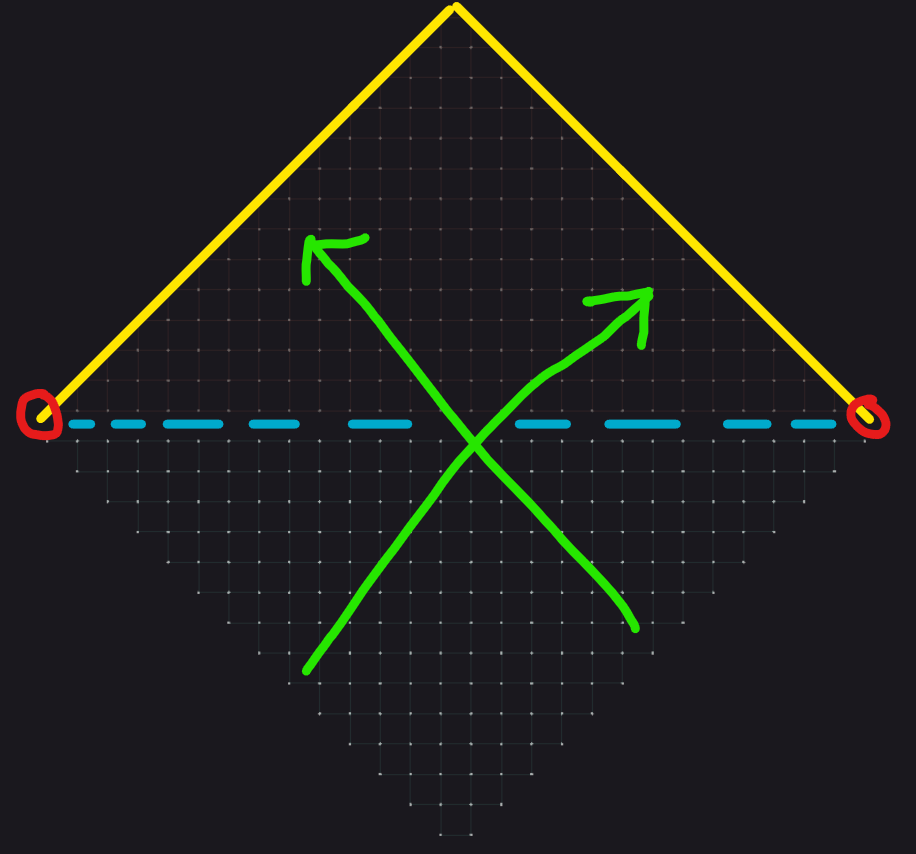

Asymmetry in Defensibility

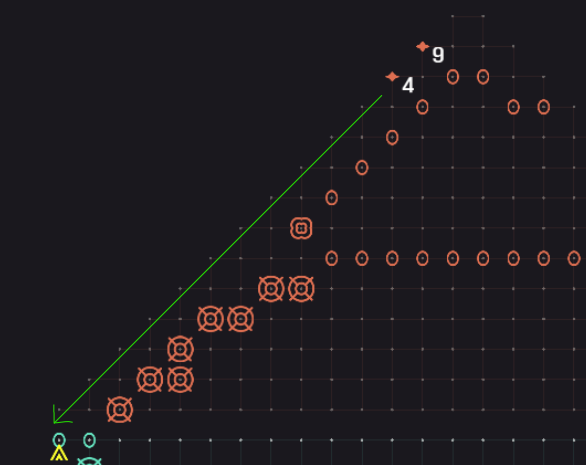

Observing the board above and playing as the player on the lower half of the board (below the blue line), we intend to score on the opponent’s diagonal edges (the yellow lines) following the directions marked out in green. We notice that given the diagonal shape of the board, the weakest parts of the board are actually the two corner locations (circled in red).

Since the oppponent is not able to place any units below the blue line (our friendly territory), there is a severe lack of defence in depth, which is exacerbated by the location’s proximity to friendly lines.

Predictable Path-Finding

Defence

By reading through the documentation, we learnt that the path-finding AI of the individual units essentially seeks out the shortest path to the opponent’s edge. This meant that as long as there was an unobstructed path to the opponent’s edge, the units would always choose that path to travel. The individual units would hence completely ignore nearby ranged enemy structures (turrets) that would impede the assaulting units from reaching the edge.

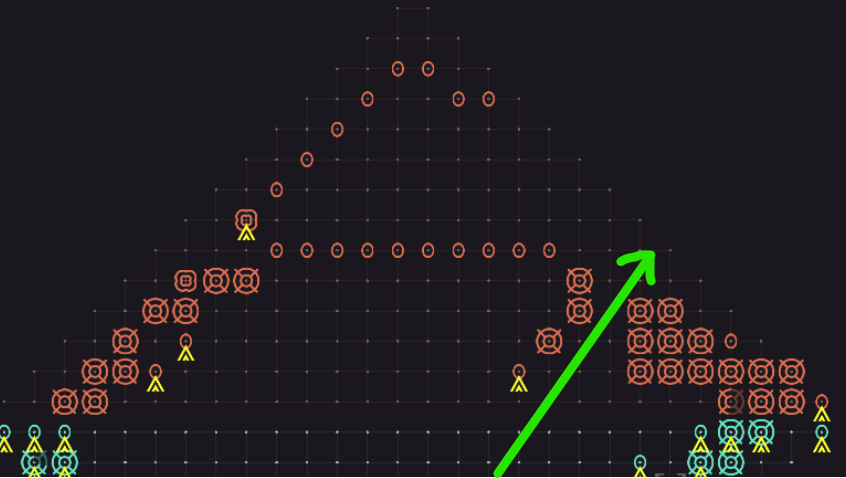

To exploit this, we designed our defence structure in such a way that we would “funnel” the enemy units through a technically open, but highly defended path. Against our funnel structure in red as seen below, the enemy assaulting units would take the green path, as it is technically clear of obstacles. However, the path travels through a heavily defended region, with a large amount of turrets (icon with red concentric circles and a cross) attriting the enemy before it can even reach the end.

This crucially allowed us to free up resource spending on defenses elsewhere, as we could predict that the enemy units would always (at least aim to) go towards that heavily protected funnel due to their path-finding design.

Attack

Finally, since we also wanted to exploit the corners of our enemy’s defences, we designed a tunnel within friendly lines such that our units would have no clear path out but to push towards the corner positions of the enemy defences at the end of the tunnel (seen in the green path below). This allowed us to focus our assaulting units on the specific corner locations on the map.

High Self-Destructing Damage Potential

In order for us to score on the targeted positions, we first had to destroy the defensive structure in that position. An important game mechanic we noted was that assaulting units that have no clear path to the enemy location would self-destruct themselves on an enemy defensive structure and generate a large amount of damage.

This mechanic allowed us to be able to reliably destroy the enemy’s defensive lines, making way for further units to score on that position. To achieve this, we separated our assaulting units into a “breaching” and “convoy” group.

Breaching Group: responsible for guaranteeing the destruction of the enemy defensive structure. I achieved this by designing a simulation to calculate the minimum number of units required to ensure a successful breach of the targeted position. This simulation had to also take into account the damage received from the turrets, as we had to ensure that enough units survived before self-destructing at the enemy structure.

Convoy Group: responsible for the actual scoring of points. Similarly, I also designed a simulation to ensure that the group size was large enough to score a minimum number of points on the enemy. Otherwise, the assault would not be useful at all.

Learning Points

After the competition deadline, my team started to notice a lot of bugs and issues with the code that we had submitted. After correcting them, we noticed that the algorithm performed far better than the version we had submitted (allowing us to achieve top 10 on the global leaderboard). This was frustrating for the team, as we knew that our strategy had the potential to do much better.

During the competition, I was primarily in charge of designing the attack strategy, while my partner worked on defence. Looking back, I recognise that taking time to integrate our two parts (defence and attack) was critical to ensuring that everything ran smoothly, and is something that I will not gloss over in the future.

Further, it was important that we did loads of testing before submitting our final product. This was difficult, as we simply did not have the time. However, this is definitely something we should work towards in the future.

Areas for Improvement

One of the key features lacking in our algorithm was the use of any machine learning and deep learning models. This was largely due to the lack of time, where we found it difficult to train a reliable model on such a complicated game in such a limited timeframe. However, examining our program, we notice that much of our macro strategies: deciding when to attack, when to rebuild defences or when to save were quite primitive and basic.

We could definitely better utilise the game state information provided to us to make such decisions with AI.